Children, indigenous communities and people of Afro descent are among the categories of people worst hit my extreme poverty levels, studies have revealed. It adds to concerns that inequality is on the rise across the continent, and governments appear to be doing little to improve the situation.

Patricia Santiaga, 30 years, is one of the 34 million Mexicans that lives in a makeshift house, made of poor materials such as cardboard and reeds in shanty towns. Her precarious living conditions cramped with her family in too little space may symbolize how many Mexicans feel: Literally trapped in poverty.

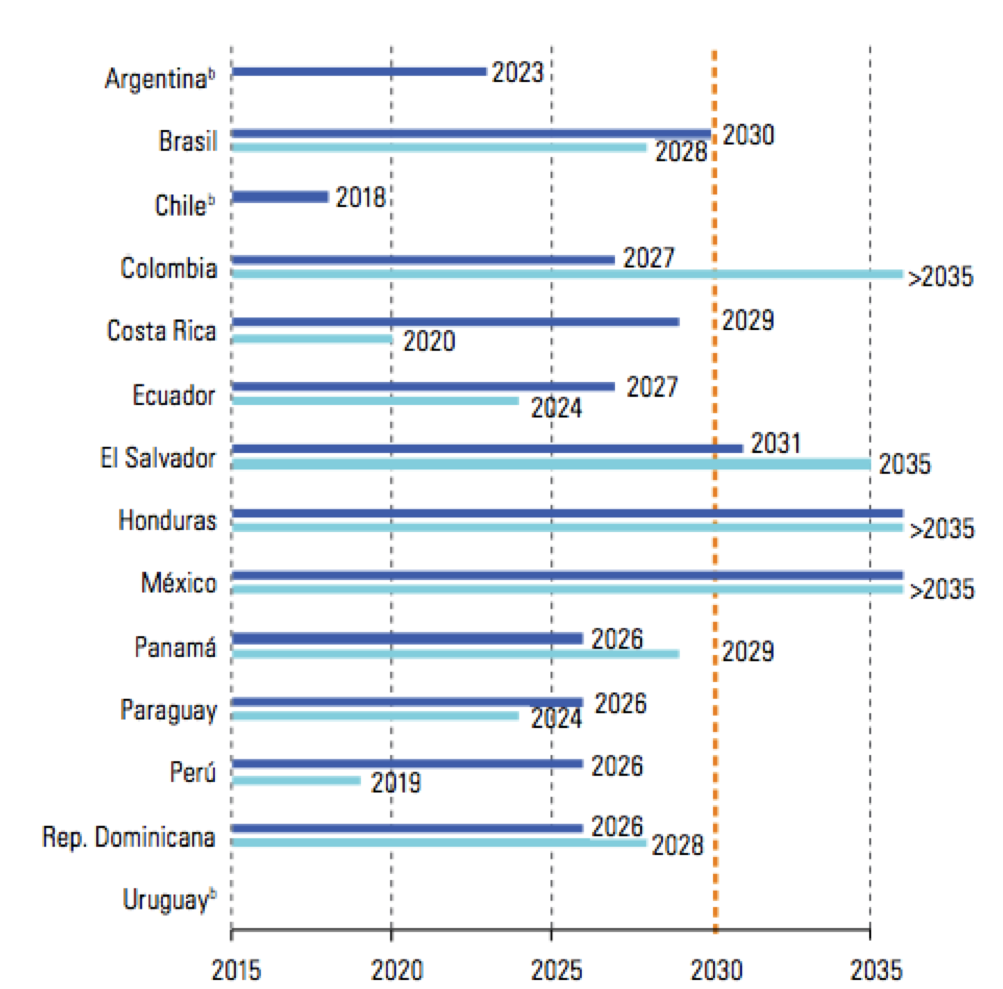

A new report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) now warns that income inequality and the amount of people living in extreme poverty are rising in Latin America. And while Mexico made some progress, it would take until 2035 until the country would reach its poverty goals, says the forecast – or until Patricia would be almost 50 years old.

Mexico is not the only country struggling with addressing rising poverty. In all of Latin America, 84 million people are still poor, according to the report. Even more alarming, 63 million live in extreme poverty, the highest number in a decade.

The adverse effects of poverty and extreme poverty are especially hitting hard vulnerable groups such as children. Taking the example of Mexico, a report by the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (Coneval) just warned in December that one million children cannot attend school because of poverty. And in Argentina, nearly half of children in urban areas live in a household that falls under the poverty line, a study by the Argentina Catholic University and the Observatory of Argentina Social Debt (ODSA) found. They are affected from issues such as risk of unsafe construction of their homes to restricted access to health services and education.

The authors also warn that some groups are suffering from barriers to the labour market, which impedes them from lifting themselves out of poverty. Structural inequalities persist that affect particularly women, people with disabilities and young people.

Put at particular disadvantage are also indigenous people and Afro-descendants. For example, if you are a member of Latin America’s 42 million indigenous people, you will be double as likely to live under the poverty line, says the ECLAC report.

Brazil has the highest inequality of all Latin America

Among all countries, Brazil is the most unequal in terms of income distribution, with a Gini coefficient of 0,54, followed by Colombia and Panamá (0,51). The indicator measures inequality from 0 (all property is distributed completely equal) to 1 (one person owns everything and the rest nothing).

While Latin America overall has been reducing its income inequality over the last years, Brazil’s inequality has been rising since 2014. According to a survey by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IGBE), a new wave of 2 million people slipped into extreme poverty within the last year, resulting in a total number of more than 15 million people.

Growing poverty and a growing economic divide of the population is one of the underlying factors many believe has contributed to the election of radical far-right Jair Bolsonaro in last year’s presidential election in Brazil.

Labour inclusion should be political priority

Governments in the region have made important progress. Overall, per capita spending on social protection and support has practically doubled between 2002 and 2016. In countries such as Chile and Uruguay, governments spend more than 2200 dollars per citizen on social policies. However, on the other end of the spectrum, Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua spend less than a tenth of this per-capita budget, the CEPAL authors say.

Furthermore, people must be registered and part of the formal labour market to access social benefits such as pension funds and insurance. Yet in many countries, a large part of the workforce is part of the informal economy. Furthermore, Alicia Bárcena, Executive Secretary of the ECLAC, said to the press that promoting labour inclusion policies such as training, work incentives and unemployment protection should be a political priority. These measures should “especially aim at the young and extremely poor population”, she recommends.